SE: The Barry Brown, Jr., Story, as Told by Others

Mar 20, 2019 | Men's Basketball, Sports Extra

By Corbin McGuire

Barry Brown, Jr. was born in St. Petersburg, Florida, on December 21, 1996, with a somewhat pre-determined life — a "plan," his father, Barry Brown, Sr., likes to call it.

Barry Jr. was going to be a college basketball player. He was going to take academics seriously. He was going to be a good person — respectful, kind, a positive light for others.

He was going to be a better Barry Brown than the first to carry that name.

"That was the plan," Barry Sr. said.

What was not on the plan? Well, that's where Barry Jr. stands now.

First Team All-Big 12. Conference Defensive Player of the Year. K-State school record holder. Big 12 Champion. Team leader. Program changer.

None of those feats could have been planned out. But all, to varying degrees, were byproducts of the initial plan. Barry Jr. just took it a step further — OK, a few steps — and made his own plan. He took advantage of the good breaks and people along the way, and he overcame the bad ones.

He let nothing and no one stop him from being a success.

"I tell him all the time, he's the best Barry Brown I know," Barry Sr. said, as his son starts his last NCAA Tournament on Friday at 1 p.m. (CT), when No. 4-seed K-State plays 13th-seeded UC Irvine in San Jose, California. "That's always been the goal."

***

Barry Jr. was raised with basketball — "There was a basketball in the crib," his father said — and without the option of working hard.

The latter was the standard in the Brown household, where Barry Sr. worked up to four jobs at certain times of his son's childhood.

Barry Sr. was hard on his son, he readily admits. Driveway practices ended in tears more than once. Barry Jr. often heard his father tell him: "You're going to either get it, or you're going to get it."

"I didn't hold back," Barry Sr. said.

Case in point: Around sixth and seventh grade, Barry Jr. had "a bad case" of asthma, his father said. While it's ironic now because he ranks second in career minutes at K-State, it was a problem back then.

At the time, Barry Sr. took his son to a specialist, who had Barry Jr. blow into a chamber to measure the strength of his lungs. He could not fill the chamber all the way up. The only way around this, Barry Sr. remembers being told, was to increase his son's V02 Max —the measurement of the maximum amount of oxygen a person can utilize during intense exercise.

The best way to do to this: Long runs.

After some coffee — a full cup for Barry Sr., and a half cup for Barry Jr. — the two ran before the sun rose. They started with two miles. Then three. Early in this process, they would be neck-and-neck at the end of each run. A few months in, Barry Jr. started laughing at his father as he blew by him down the stretch.

"By the end of the year," Barry Sr. said, "he was blowing the top off that chamber."

Barry Jr. grew to enjoy hard work. Barry Sr. thinks of two stories when his son's work ethic no longer became a concern.

The first took place one summer after a couple of hurricanes or tropical storms hit the area. A friend of Barry Sr.'s needed help picking up tree limbs and debris. So, he hired Barry Jr. for $100. From then on, any time a storm hit the area, Barry Jr. called his father's friend to earn some extra money.

"He's self-initiated," Barry Sr. said. "That let me know, from a work standpoint, I wasn't going to have to worry about it."

The second story came after a divorce led to a "rough spell at the house," Barry Sr. said.

A school principal, Barry Sr. needed to make some extra money at the time. He picked up a job throwing newspapers. On the weekends or weekdays when school was out, Barry Jr. would help his father, dashing around apartment complexes to distribute newspapers at hundreds of door steps.

"All I had to do was get him a McGriddle with sausage and egg at the end of every route. But I'll never, ever forget that," Barry Sr. said. "He never, ever complained. He just took care of business."

On the basketball court, Barry Jr. followed suit. When it came down to doing the extra work, Barry Sr. said his son "took the choice away" from him around his freshman year of high school.

Barry Jr. began to live and breathe basketball. He also started to play on Each1Teach1, one of the top AAU programs in the country. It's produced NBA players such as Ben Simmons, D'Angelo Russell, Antonio Blakeney, Austin Rivers and Jonathan Isaac.

How he got on the team took a little good fortune, paired with his hard work. It led to K-State finding him, also with a little bit of luck.

***

Anthony Lawrence, Sr. remembers being in the waiting room the day Barry Jr. was born. Barry Sr. held his best friend's son, Anthony Jr., born about three months earlier.

The two fathers, who consider each other brothers, coached their sons on the same youth teams for years. Barry Jr. and Anthony Jr. also developed a family-like friendship. They each had a plan— Anthony Sr. called it a "blueprint" — to play college basketball mapped out for them since 1992, but they got there in different ways.

Anthony Jr. grew to 6-foot-7 and wound up at Miami, where he just finished a four-year career. Barry Jr. was a scrawny 6-foot-3 and had to force his way onto the recruiting scene.

Each1Teach1 wanted Anthony Jr. The program also needed a guard, but the coaches were not sold on Barry Jr. His recruiting rankings were nothing impressive, but each guard brought in with more stars and Internet hype, Barry Jr. just beat him out.

"He absolutely destroyed people," Anthony Sr. said in a phone interview. "He destroyed anybody that came in there."

Barry Jr. did get some help, however.

When Barry Sr. had to work, Anthony Sr. would pick up Barry Jr. to go to the team's practices in Orlando. At one point, the team was debating between keeping him and another guard Anthony Sr. also picked up on the way.

On one drive, Anthony Sr.'s thoughts about Barry Jr.'s future got the best of him.

"As I'm driving over, I'm thinking about it, like, 'I have my nephew and my son in the car, and I'm going to pick up another kid to compete with him for his spot on this AAU program?'" Anthony Sr. said. "As I got to the exit, I pretended I missed it. I kept going."

As a result, Barry Jr. kept going to Each1Teach1 practices. His defense took off under his high school coach, Larry Murphy, and soon Barry Jr. asked to guard the best players on the AAU circuit, which earned him minutes off the bench of a loaded team.

It's also how K-State first found Barry Jr.

He was playing on the 16-and-under team when K-State assistant coach Chester Frazier was recruiting his teammate Fletcher McGee.

"The more I started watching their team, Barry became more of the guy I thought we would need," Frazier said.

The stars aligned again when Frazier sent K-State head coach Bruce Weber down to Gibbs High School to recruit a post, not knowing that's where Barry Jr. was playing. Weber returned more impressed by the playmaking guard. So, he sent Frazier back to Florida. Frazier watched Barry Jr. work out one day at 6 a.m.

He saw enough.

"I told Coach we need to get all over this kid. I just saw something in him. I thought he could be special," Frazier said. "My hunch was right."

***

Maryclare Wheeler's first memory of Barry Jr. is of him speeding through the Vanier Family Football Complex's academics area on his hoverboard. A graduate assistant in academics and student-athlete services at the time, Wheeler had to yell at him to get off of his infamous transportation.

In a way, the story sums up Barry Jr.'s approach to academics his first two years at K-State: Go fast with little effort. The fall of his junior year, everything changed.

"That semester, Barry really decided that he was going to make academics a priority," Wheeler, now the men's basketball academics counselor, said. "We experimented with different methods that worked for him, and that is the minute I found that Barry Brown likes a list."

Wheeler began texting him a picture of a written to-do list for each week. It became a challenge for Barry Jr., who hadto be the person to physically cross out each item on the list in her office.

He came to find that the sooner he finished his list, the more time he could spend in the practice facility. He even shifted toward an online class schedule, so he could organize his day to maximize his basketball hours.

"You could watch it all fall in place. He figured out how to do his academics, how to balance both, and then you could see his game followed with it," Wheeler said. "A lot of guys are trying to get on the Barry Brown plan."

Last fall, he took 19 credit hours so that he could wrap up his degree this spring with a mere six hours. He approached academics as he did basketball: Nobody was going to outwork him.

In a biochemistry class last fall, he had to draw chemical structures for an assignment. Before drawing his, Barry Jr. would visually analyze at the structures for five minutes, draw them for practice at least three times on scrap paper and then do the real ones.

"That is signature Barry Brown," Wheeler said. "He's going to practice a million times before he's going to do it, and then he's going to do it right."

With academics figured out, Barry Jr. redefined the term gym rat.

His coaches might see him shooting when they came in at 8 a.m., and K-State's mangers could see him shooting at 1 a.m. In between, when he was not focused on his school list, he would be in the coaches' offices, picking their brain or watching film.

"His junior year, he took it to a new level," Frazier said of Barry Jr.'s drive. "This year has been extreme-extreme. He's definitely first one in and last to leave."

"I haven't seen anybody work like him. He's always in the gym," junior Xavier Sneed added. "Any time I think I might have it to myself, he's in there already."

K-State assistant coach Brad Korn relates it to a philosophy made famous in the basketball world by Kobe Bryant, who wore the No. 24 the latter part of his career. He picked that number as a reminder to make the most out of each 24-hour day.

"Some guys choose to sleep," Korn said. "Barry chooses to wake up in the morning, to get work done."

***

For the most part, Barry Jr.'s other traits flow from his hard work, from the initial plan.

The confidence that caused him to raise his hand as a freshman at K-State when Weber asked who was going to be the team's defensive stopper, or to worry last September, when being sized for his class ring, about which finger his Big 12 Championship ring would go on, that confidence has been there all along.

Barry Sr. remembers seeing this confidence years ago, when he picked him up from a weeklong football camp. As they walked back to the car, another player at the camp started trash talking Barry Jr. from nearby. He called Barry Jr. "soft" and "sorry."

Barry Jr. did not even acknowledge him. Barry Sr. questioned his son.

Why aren't you yelling back? Why aren't you defending yourself?

"He was, like, 'Dad, I was cooking him all week. Why do I need to say something to this dude? He's trash. He's terrible. I've been beating him all week,'" Barry Sr. recalled. "That's confidence. When you don't even feel obligated amongst your peers to say something to this dude who I know is beneath me. That's where he was a little bit different."

Barry Jr.'s competitiveness is different in that it has no off switch.

When he ran out of light to play basketball in the driveway as a child, he pulled out a Monopoly board and challenged anyone in the house to a game. He does the same now with his teammates and holds family tournaments when he's back home.

He's competitive at making smoothies. He even tried Pure Barr to prove to Ija Hawthorne, a vice principal at Gibbs High School and motherly figure in his life, he could do it.

"He talked so much trash about, 'Oh, that's no big deal. I'm lifting, blah, blah, blah,' Well, he went to this class, and it about killed him," Hawthorne said, laughing. "He's gone four times with me."

Hawthorne, whose office was located nearest to the gym in Gibbs High School, saw Barry Jr.'s leadership and determination develop firsthand. She witnessed him coerce his teammates into extra shooting and work, without them even knowing it.

At K-State, Brown has done the same things. Multiple times, he's helped keep his team from sinking in key moments.

There was the players' only practice he organized after Kamau Stokes broke his foot last season. The next game, he broke out for 38 points in a win against Oklahoma State, when he had the flu.

This season, there was his halftime speech at home against West Virginia that helped spark a school-record comeback. It altered the course of the team's season as well.

"He's respected. For one, that makes a leader. Two, he not only talks it, but he walks it," Frazier said. "He doesn't take shortcuts, he doesn't take plays off, he practices hard every day. You can't ask more of a leader."

Barry Jr. wants the ball in his hands in crucial moments because he knows he's prepared for them. The layup against Kentucky in last year's Sweet 16 matchup is a prime example. So are the two game-winners in one week this season against West Virginia and Iowa State.

"He's really just been the heartbeat of the program," Korn said. "He's been the one guy that said, 'I'm not going have losing seasons. I'm going to have an unbelievable career. I'm going to leave a legacy.' And he's done that."

He ranks in the top 10 in 15 different categories at K-State, including first in steals, consecutive games played and started, along with fifth in career points. His accomplishments have been matched by his humility and love for K-State, however. He signs autographs after nearly every game. He even went out of his way on social media to get a young fan from Valley Center tickets and a ride to a game this season.

He's also fun-loving and considerate. He's eager to pose as a manikin to scare his teammates and head coach. When asked to do a photoshoot with a goat or sleeping with the Big 12 Championship trophy, he goes with it. He's often brought Wheeler a smoothie as a pick-me-up, just like he used to bring sunflower seeds to Hawthorne, whose birthday he never forgets.

He's become the plan his father thought of 22 years ago, and so much more.

"The stars were in alignment," Barry Sr. said. "And he didn't stop putting in the work."

Barry Brown, Jr. was born in St. Petersburg, Florida, on December 21, 1996, with a somewhat pre-determined life — a "plan," his father, Barry Brown, Sr., likes to call it.

Barry Jr. was going to be a college basketball player. He was going to take academics seriously. He was going to be a good person — respectful, kind, a positive light for others.

He was going to be a better Barry Brown than the first to carry that name.

"That was the plan," Barry Sr. said.

What was not on the plan? Well, that's where Barry Jr. stands now.

First Team All-Big 12. Conference Defensive Player of the Year. K-State school record holder. Big 12 Champion. Team leader. Program changer.

None of those feats could have been planned out. But all, to varying degrees, were byproducts of the initial plan. Barry Jr. just took it a step further — OK, a few steps — and made his own plan. He took advantage of the good breaks and people along the way, and he overcame the bad ones.

He let nothing and no one stop him from being a success.

"I tell him all the time, he's the best Barry Brown I know," Barry Sr. said, as his son starts his last NCAA Tournament on Friday at 1 p.m. (CT), when No. 4-seed K-State plays 13th-seeded UC Irvine in San Jose, California. "That's always been the goal."

***

Barry Jr. was raised with basketball — "There was a basketball in the crib," his father said — and without the option of working hard.

The latter was the standard in the Brown household, where Barry Sr. worked up to four jobs at certain times of his son's childhood.

Barry Sr. was hard on his son, he readily admits. Driveway practices ended in tears more than once. Barry Jr. often heard his father tell him: "You're going to either get it, or you're going to get it."

"I didn't hold back," Barry Sr. said.

Case in point: Around sixth and seventh grade, Barry Jr. had "a bad case" of asthma, his father said. While it's ironic now because he ranks second in career minutes at K-State, it was a problem back then.

At the time, Barry Sr. took his son to a specialist, who had Barry Jr. blow into a chamber to measure the strength of his lungs. He could not fill the chamber all the way up. The only way around this, Barry Sr. remembers being told, was to increase his son's V02 Max —the measurement of the maximum amount of oxygen a person can utilize during intense exercise.

The best way to do to this: Long runs.

After some coffee — a full cup for Barry Sr., and a half cup for Barry Jr. — the two ran before the sun rose. They started with two miles. Then three. Early in this process, they would be neck-and-neck at the end of each run. A few months in, Barry Jr. started laughing at his father as he blew by him down the stretch.

"By the end of the year," Barry Sr. said, "he was blowing the top off that chamber."

Barry Jr. grew to enjoy hard work. Barry Sr. thinks of two stories when his son's work ethic no longer became a concern.

The first took place one summer after a couple of hurricanes or tropical storms hit the area. A friend of Barry Sr.'s needed help picking up tree limbs and debris. So, he hired Barry Jr. for $100. From then on, any time a storm hit the area, Barry Jr. called his father's friend to earn some extra money.

"He's self-initiated," Barry Sr. said. "That let me know, from a work standpoint, I wasn't going to have to worry about it."

The second story came after a divorce led to a "rough spell at the house," Barry Sr. said.

A school principal, Barry Sr. needed to make some extra money at the time. He picked up a job throwing newspapers. On the weekends or weekdays when school was out, Barry Jr. would help his father, dashing around apartment complexes to distribute newspapers at hundreds of door steps.

"All I had to do was get him a McGriddle with sausage and egg at the end of every route. But I'll never, ever forget that," Barry Sr. said. "He never, ever complained. He just took care of business."

On the basketball court, Barry Jr. followed suit. When it came down to doing the extra work, Barry Sr. said his son "took the choice away" from him around his freshman year of high school.

Barry Jr. began to live and breathe basketball. He also started to play on Each1Teach1, one of the top AAU programs in the country. It's produced NBA players such as Ben Simmons, D'Angelo Russell, Antonio Blakeney, Austin Rivers and Jonathan Isaac.

How he got on the team took a little good fortune, paired with his hard work. It led to K-State finding him, also with a little bit of luck.

***

Anthony Lawrence, Sr. remembers being in the waiting room the day Barry Jr. was born. Barry Sr. held his best friend's son, Anthony Jr., born about three months earlier.

The two fathers, who consider each other brothers, coached their sons on the same youth teams for years. Barry Jr. and Anthony Jr. also developed a family-like friendship. They each had a plan— Anthony Sr. called it a "blueprint" — to play college basketball mapped out for them since 1992, but they got there in different ways.

Anthony Jr. grew to 6-foot-7 and wound up at Miami, where he just finished a four-year career. Barry Jr. was a scrawny 6-foot-3 and had to force his way onto the recruiting scene.

Each1Teach1 wanted Anthony Jr. The program also needed a guard, but the coaches were not sold on Barry Jr. His recruiting rankings were nothing impressive, but each guard brought in with more stars and Internet hype, Barry Jr. just beat him out.

"He absolutely destroyed people," Anthony Sr. said in a phone interview. "He destroyed anybody that came in there."

Barry Jr. did get some help, however.

When Barry Sr. had to work, Anthony Sr. would pick up Barry Jr. to go to the team's practices in Orlando. At one point, the team was debating between keeping him and another guard Anthony Sr. also picked up on the way.

On one drive, Anthony Sr.'s thoughts about Barry Jr.'s future got the best of him.

"As I'm driving over, I'm thinking about it, like, 'I have my nephew and my son in the car, and I'm going to pick up another kid to compete with him for his spot on this AAU program?'" Anthony Sr. said. "As I got to the exit, I pretended I missed it. I kept going."

As a result, Barry Jr. kept going to Each1Teach1 practices. His defense took off under his high school coach, Larry Murphy, and soon Barry Jr. asked to guard the best players on the AAU circuit, which earned him minutes off the bench of a loaded team.

It's also how K-State first found Barry Jr.

He was playing on the 16-and-under team when K-State assistant coach Chester Frazier was recruiting his teammate Fletcher McGee.

"The more I started watching their team, Barry became more of the guy I thought we would need," Frazier said.

The stars aligned again when Frazier sent K-State head coach Bruce Weber down to Gibbs High School to recruit a post, not knowing that's where Barry Jr. was playing. Weber returned more impressed by the playmaking guard. So, he sent Frazier back to Florida. Frazier watched Barry Jr. work out one day at 6 a.m.

He saw enough.

"I told Coach we need to get all over this kid. I just saw something in him. I thought he could be special," Frazier said. "My hunch was right."

***

Maryclare Wheeler's first memory of Barry Jr. is of him speeding through the Vanier Family Football Complex's academics area on his hoverboard. A graduate assistant in academics and student-athlete services at the time, Wheeler had to yell at him to get off of his infamous transportation.

In a way, the story sums up Barry Jr.'s approach to academics his first two years at K-State: Go fast with little effort. The fall of his junior year, everything changed.

"That semester, Barry really decided that he was going to make academics a priority," Wheeler, now the men's basketball academics counselor, said. "We experimented with different methods that worked for him, and that is the minute I found that Barry Brown likes a list."

Wheeler began texting him a picture of a written to-do list for each week. It became a challenge for Barry Jr., who hadto be the person to physically cross out each item on the list in her office.

He came to find that the sooner he finished his list, the more time he could spend in the practice facility. He even shifted toward an online class schedule, so he could organize his day to maximize his basketball hours.

"You could watch it all fall in place. He figured out how to do his academics, how to balance both, and then you could see his game followed with it," Wheeler said. "A lot of guys are trying to get on the Barry Brown plan."

Last fall, he took 19 credit hours so that he could wrap up his degree this spring with a mere six hours. He approached academics as he did basketball: Nobody was going to outwork him.

In a biochemistry class last fall, he had to draw chemical structures for an assignment. Before drawing his, Barry Jr. would visually analyze at the structures for five minutes, draw them for practice at least three times on scrap paper and then do the real ones.

"That is signature Barry Brown," Wheeler said. "He's going to practice a million times before he's going to do it, and then he's going to do it right."

With academics figured out, Barry Jr. redefined the term gym rat.

His coaches might see him shooting when they came in at 8 a.m., and K-State's mangers could see him shooting at 1 a.m. In between, when he was not focused on his school list, he would be in the coaches' offices, picking their brain or watching film.

"His junior year, he took it to a new level," Frazier said of Barry Jr.'s drive. "This year has been extreme-extreme. He's definitely first one in and last to leave."

"I haven't seen anybody work like him. He's always in the gym," junior Xavier Sneed added. "Any time I think I might have it to myself, he's in there already."

K-State assistant coach Brad Korn relates it to a philosophy made famous in the basketball world by Kobe Bryant, who wore the No. 24 the latter part of his career. He picked that number as a reminder to make the most out of each 24-hour day.

"Some guys choose to sleep," Korn said. "Barry chooses to wake up in the morning, to get work done."

***

For the most part, Barry Jr.'s other traits flow from his hard work, from the initial plan.

The confidence that caused him to raise his hand as a freshman at K-State when Weber asked who was going to be the team's defensive stopper, or to worry last September, when being sized for his class ring, about which finger his Big 12 Championship ring would go on, that confidence has been there all along.

Barry Sr. remembers seeing this confidence years ago, when he picked him up from a weeklong football camp. As they walked back to the car, another player at the camp started trash talking Barry Jr. from nearby. He called Barry Jr. "soft" and "sorry."

Barry Jr. did not even acknowledge him. Barry Sr. questioned his son.

Why aren't you yelling back? Why aren't you defending yourself?

"He was, like, 'Dad, I was cooking him all week. Why do I need to say something to this dude? He's trash. He's terrible. I've been beating him all week,'" Barry Sr. recalled. "That's confidence. When you don't even feel obligated amongst your peers to say something to this dude who I know is beneath me. That's where he was a little bit different."

Barry Jr.'s competitiveness is different in that it has no off switch.

When he ran out of light to play basketball in the driveway as a child, he pulled out a Monopoly board and challenged anyone in the house to a game. He does the same now with his teammates and holds family tournaments when he's back home.

He's competitive at making smoothies. He even tried Pure Barr to prove to Ija Hawthorne, a vice principal at Gibbs High School and motherly figure in his life, he could do it.

"He talked so much trash about, 'Oh, that's no big deal. I'm lifting, blah, blah, blah,' Well, he went to this class, and it about killed him," Hawthorne said, laughing. "He's gone four times with me."

Hawthorne, whose office was located nearest to the gym in Gibbs High School, saw Barry Jr.'s leadership and determination develop firsthand. She witnessed him coerce his teammates into extra shooting and work, without them even knowing it.

At K-State, Brown has done the same things. Multiple times, he's helped keep his team from sinking in key moments.

There was the players' only practice he organized after Kamau Stokes broke his foot last season. The next game, he broke out for 38 points in a win against Oklahoma State, when he had the flu.

This season, there was his halftime speech at home against West Virginia that helped spark a school-record comeback. It altered the course of the team's season as well.

"He's respected. For one, that makes a leader. Two, he not only talks it, but he walks it," Frazier said. "He doesn't take shortcuts, he doesn't take plays off, he practices hard every day. You can't ask more of a leader."

Barry Jr. wants the ball in his hands in crucial moments because he knows he's prepared for them. The layup against Kentucky in last year's Sweet 16 matchup is a prime example. So are the two game-winners in one week this season against West Virginia and Iowa State.

"He's really just been the heartbeat of the program," Korn said. "He's been the one guy that said, 'I'm not going have losing seasons. I'm going to have an unbelievable career. I'm going to leave a legacy.' And he's done that."

He ranks in the top 10 in 15 different categories at K-State, including first in steals, consecutive games played and started, along with fifth in career points. His accomplishments have been matched by his humility and love for K-State, however. He signs autographs after nearly every game. He even went out of his way on social media to get a young fan from Valley Center tickets and a ride to a game this season.

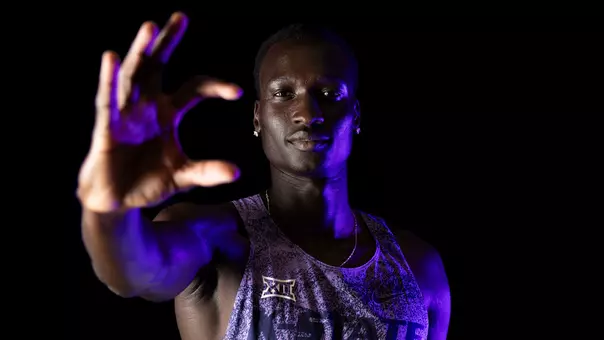

He's also fun-loving and considerate. He's eager to pose as a manikin to scare his teammates and head coach. When asked to do a photoshoot with a goat or sleeping with the Big 12 Championship trophy, he goes with it. He's often brought Wheeler a smoothie as a pick-me-up, just like he used to bring sunflower seeds to Hawthorne, whose birthday he never forgets.

He's become the plan his father thought of 22 years ago, and so much more.

"The stars were in alignment," Barry Sr. said. "And he didn't stop putting in the work."

Players Mentioned

K-State Men's Basketball | Recap vs West Virginia

Friday, March 06

K-State Men's Basketball | Interim Head Coach Driscoll Press Conference (West Virginia)

Wednesday, March 04

K-State Men's Basketball | Khamari McGriff & Nate Johnson Postgame Press Conference (West Virginia)

Wednesday, March 04

K-State Men's Basketball | Game Highlights vs West Virginia

Wednesday, March 04