A K-State Trailblazer That Lived to Serve Others

Aug 03, 2022 | Track & Field, Sports Extra

By: D. Scott Fritchen

It had been many years since Dick Towers spoke to his former Kansas State teammate and good friend. But Towers was not surprised to learn that Johnnie Lee Caldwell, who passed away on July 19 at age 94, had positively impacted the lives of hundreds of young people at Kalamazoo, Michigan, area schools, ultimately as principal at Kalamazoo Central High School.

"Johnnie was a very positive, positive person," Towers said. "He was an excellent student. If he was in school administration, he would've been excellent. He was soft spoken, had a really dry sense of humor, and was a really neat guy. He had a great life, I'm sure."

Caldwell played basketball and ran track at Sumner High School in Kansas City before graduating and joining the U.S. Army. After a two-year enlistment, he used the G.I. Bill to attend K-State. Caldwell, Towers, Jerry Rowe, and Thane Baker won the 1953 Big Seven Conference title in the mile relay.

"We won the conference championship with Johnnie in the mile relay," Towers said. "He ran a quarter mile, I ran a quarter mile, and Thane Baker anchored it."

Caldwell was one of the first African American student-athletes at K-State.

"Sure, I'd consider Johnnie a trailblazer," Towers said.

However, Caldwell dealt with injustice at times away from Manhattan.

"Ward Haylett was our coach, and we had a number of relay teams, but John couldn't run when we went down to New Orleans to compete in the Sugar Bowl relays," Towers said. "Our relay team won the conference championship the year before, but they wouldn't allow him to compete. He was a very important part of our track team."

Another time, Towers remembered that Caldwell faced discrimination in a Kansas City restaurant.

"We went to a conference meet at Ames, Iowa, and Johnnie was a leader our senior year and drove the university car," Tower said. "Four of us headed to Ames. Ward Haylett told us when we drove past Kansas City to stop and eat. The place I ate at all the time in Kansas City was the cafeteria downtown at 12th and Central. They said they didn't serve Blacks there.

"There's no question in my mind that Johnnie Caldwell didn't like his situation where he couldn't compete and couldn't get involved because he was Black, but I think he grew up in an outstanding family and they believed in hard work and that you make the most out of situations, and I believe he did, and because of that he succeeded when he had his opportunity."

"Johnnie was also a very good basketball player," Towers added. "He played on Kappa Alpha Psi and there were a number of really good athletes on the team. Johnnie was the best player on the team."

The eldest of nine children, Caldwell was born September 16, 1927, in Kansas City, Kansas, the son of a steelworker. With the desire to become a teacher, Caldwell earned a bachelor's degree in education and recreation, and a master's degree in physical education at K-State.

Upon graduation, he became associate director of the Douglass Community Association in Manhattan.

He married his wife Irma in 1956 and relocated as associate director of the Douglass Community Association in Kalamazoo. Caldwell, who operated a pest control business while leading the Douglass Community Association, rose to become executive director of that organization. He was an all-around leader for that social service and recreational agency, doubling as a lifeguard, swimming instructor, playground supervisor, and coach for its baseball, softball, and basketball clinics.

He left the position in 1963 to become an educator at Milwood Junior High School.

Caldwell was a life-long learner and an advocate for civil rights. He pushed to see more women hired as coaches of girls' sports teams. In 1965, he helped establish a fund to promote justice for African Americans in Selma, Alabama, and he was involved for years with the Metropolitan Kalamazoo Branch of the NAACP.

Caldwell was promoted to Kalamazoo Central High School assistant principal on April 8, 1968 — four days after the assassination of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Caldwell helped guide students through several years of racial unrest, and he was among local African American leaders recognized for doing so.

He became Oakwood Junior High School principal in 1973 as school desegregation caused unrest in the Kalamazoo community. He described the conditions as "riotous" that year, but he spent the summer visiting the homes of hostile parents to help effect change.

Eight years later, he was named Hillside Junior High School principal, then became Kalamazoo Central High School principal in 1985.

"Johnnie was a top-notch, really outstanding person," Towers said. "He was just a really good friend and a good outstanding young man."

It had been many years since Dick Towers spoke to his former Kansas State teammate and good friend. But Towers was not surprised to learn that Johnnie Lee Caldwell, who passed away on July 19 at age 94, had positively impacted the lives of hundreds of young people at Kalamazoo, Michigan, area schools, ultimately as principal at Kalamazoo Central High School.

"Johnnie was a very positive, positive person," Towers said. "He was an excellent student. If he was in school administration, he would've been excellent. He was soft spoken, had a really dry sense of humor, and was a really neat guy. He had a great life, I'm sure."

Caldwell played basketball and ran track at Sumner High School in Kansas City before graduating and joining the U.S. Army. After a two-year enlistment, he used the G.I. Bill to attend K-State. Caldwell, Towers, Jerry Rowe, and Thane Baker won the 1953 Big Seven Conference title in the mile relay.

"We won the conference championship with Johnnie in the mile relay," Towers said. "He ran a quarter mile, I ran a quarter mile, and Thane Baker anchored it."

Caldwell was one of the first African American student-athletes at K-State.

"Sure, I'd consider Johnnie a trailblazer," Towers said.

However, Caldwell dealt with injustice at times away from Manhattan.

"Ward Haylett was our coach, and we had a number of relay teams, but John couldn't run when we went down to New Orleans to compete in the Sugar Bowl relays," Towers said. "Our relay team won the conference championship the year before, but they wouldn't allow him to compete. He was a very important part of our track team."

Another time, Towers remembered that Caldwell faced discrimination in a Kansas City restaurant.

"We went to a conference meet at Ames, Iowa, and Johnnie was a leader our senior year and drove the university car," Tower said. "Four of us headed to Ames. Ward Haylett told us when we drove past Kansas City to stop and eat. The place I ate at all the time in Kansas City was the cafeteria downtown at 12th and Central. They said they didn't serve Blacks there.

"There's no question in my mind that Johnnie Caldwell didn't like his situation where he couldn't compete and couldn't get involved because he was Black, but I think he grew up in an outstanding family and they believed in hard work and that you make the most out of situations, and I believe he did, and because of that he succeeded when he had his opportunity."

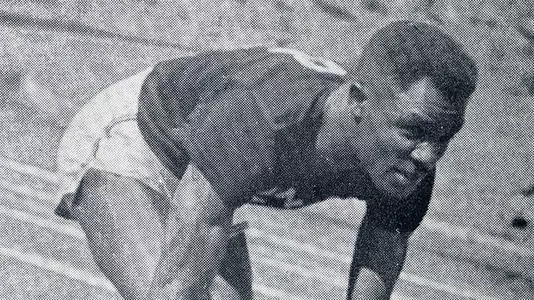

Johnnie Caldwell (middle row, fourth from left) pictured in this 1954 team photo

"Johnnie was also a very good basketball player," Towers added. "He played on Kappa Alpha Psi and there were a number of really good athletes on the team. Johnnie was the best player on the team."

The eldest of nine children, Caldwell was born September 16, 1927, in Kansas City, Kansas, the son of a steelworker. With the desire to become a teacher, Caldwell earned a bachelor's degree in education and recreation, and a master's degree in physical education at K-State.

Upon graduation, he became associate director of the Douglass Community Association in Manhattan.

He married his wife Irma in 1956 and relocated as associate director of the Douglass Community Association in Kalamazoo. Caldwell, who operated a pest control business while leading the Douglass Community Association, rose to become executive director of that organization. He was an all-around leader for that social service and recreational agency, doubling as a lifeguard, swimming instructor, playground supervisor, and coach for its baseball, softball, and basketball clinics.

He left the position in 1963 to become an educator at Milwood Junior High School.

Caldwell was a life-long learner and an advocate for civil rights. He pushed to see more women hired as coaches of girls' sports teams. In 1965, he helped establish a fund to promote justice for African Americans in Selma, Alabama, and he was involved for years with the Metropolitan Kalamazoo Branch of the NAACP.

Caldwell was promoted to Kalamazoo Central High School assistant principal on April 8, 1968 — four days after the assassination of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Caldwell helped guide students through several years of racial unrest, and he was among local African American leaders recognized for doing so.

He became Oakwood Junior High School principal in 1973 as school desegregation caused unrest in the Kalamazoo community. He described the conditions as "riotous" that year, but he spent the summer visiting the homes of hostile parents to help effect change.

Eight years later, he was named Hillside Junior High School principal, then became Kalamazoo Central High School principal in 1985.

"Johnnie was a top-notch, really outstanding person," Towers said. "He was just a really good friend and a good outstanding young man."

K-State Athletics | Ask the A.D. with Gene Taylor - Jan. 30, 2026

Friday, January 30

K-State Women's Basketball | Game Replay vs Colorado - January 29, 2026

Friday, January 30

K-State Women's Basketball | Coach Mittie Press Conference vs Colorado

Friday, January 30

K-State Women's Basketball | Athletes Press Conference vs Colorado

Friday, January 30